When Clifford “Goldie” Price stepped out of the dim light of London’s underground in 1995 with ‘Timeless’, he did more than issue a debut album; he delivered an audacious act of translation. He took a music that had been chiefly practiced in warehouses and tiny clubs (jungle and drum & bass, music of chopped breaks, bass weight and nocturnal velocity) and rewired it for an emotional register that felt almost orchestral.

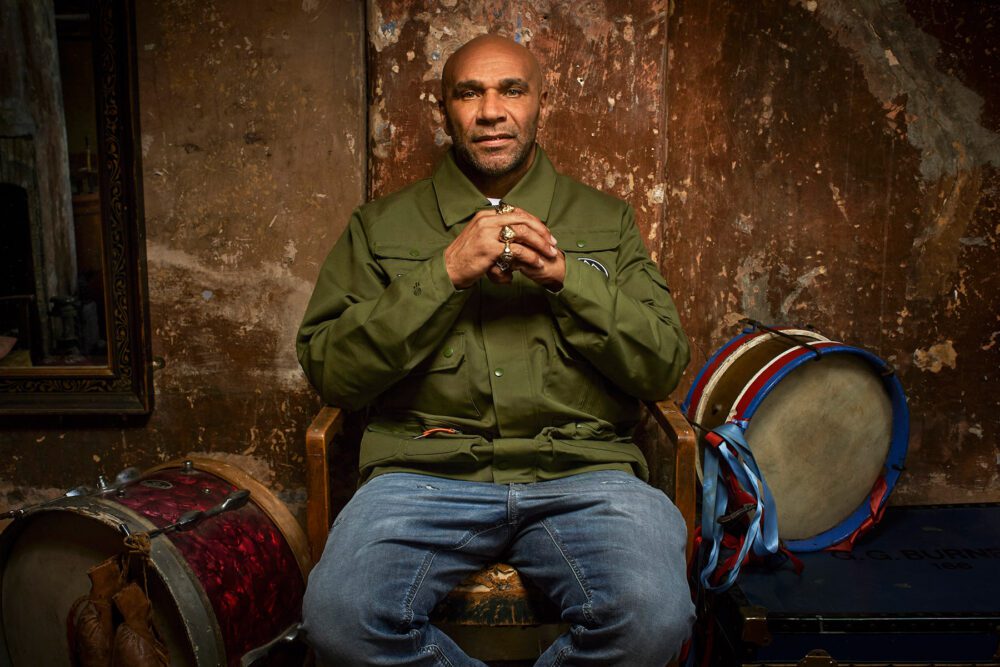

Photo Credit: Lawrence Watson

The record arrived as a double-disc statement, a map of tension and release that threaded raw club science with soulful vocals, sampled echoes of Black music history, and the kind of studio ambition usually reserved for rock operas. It entered the UK Albums Chart at number seven and, in doing so, announced drum & bass as a language capable of telling stories as large as any British album of the decade.

To understand ‘Timeless’ is to understand the alchemy of a particular place and moment. Goldie had cut his teeth as a graffiti artist and a self-styled hustler of the music scene; by the early 1990s, he was one of the engine rooms of a movement that was developing its own sonic architecture. Metalheadz—his label and ethos, co-built with DJs Kemistry and Storm—ran a Sunday residency at Hoxton’s Blue Note that read like a conservatory for a new set of musical instincts: long, precise DJ sets, dubplate culture, and a conspiratorial energy that would harden into community myth. Those nights were less parties than incubators, and the network they produced (Grooverider, Dillinja, Photek, 4hero) would be the scaffolding for ‘Timeless’.

The album’s construction was collaborative in ways that matter. Goldie brought the visions, the moods, the chapters, and the obsession with emotional sweep, while Rob Playford, the technical wizard behind Moving Shadow, translated those ideas into programming and mix decisions that could survive both on the club floor and in headphones. Dillinja’s engineering fingerprints, the textural input from 4hero’s Dego and Marc Mac, and the luminous vocal work of Diane Charlemagne and Lorna Harris completed a constellation of contributors whose skillsets pulled the music into an uncommon, almost cinematic clarity. The record’s centerpiece (a 21-minute title suite that contains ‘Inner City Life’) was not a single meant for casual radio play so much as a staged set-piece: here was drum & bass thinking like a symphony, moving through vignettes of heat, pressure, and a yearning for refuge.

If there is a thin place on ‘Timeless’, it is the seam between the streets and the score. ‘Inner City Life’—the suite’s most famous movement—layers Diane Charlemagne’s voice like a salvific force over jagged amen breaks, sub-bass swells, and stretched orchestral fragments. Its harmonics feel like sanctuary; its rhythmology insists on immediate bodily response. Critics likened the track to everything from a ghetto-blues elegy to jungle’s answer to revered pop orchestrations; DJs named it among the most formative tracks that showed drum & bass could carry the same emotional heft as the kind of post-Madchester, trip-hop soul that had dominated serious listening rooms. Its genesis also speaks to Goldie’s producerly curiosity: the record’s sonic language incorporates samples and time-stretch techniques—signatures of a studio culture that was beginning to exploit digital tools to recontextualise grooves.

Away from the suite’s apex, the album moves like a restless city at night. ‘Angel’ folds a more direct melodic tenderness into the rush, its piano chords and vocal registers softening the record’s edges; ‘Kemistry’ reads as both homage and elegy, named for the DJ Kemi Olusanya who had been integral to Goldie’s world; ‘You & Me’, ‘Sea of Tears’ and ‘Sensual’ each find different balances between swing and lament, between chopped percussion and long, airy pads. The sequencing matters: Timeless refuses the quick turnaround of single-minded peak-hour tools, preferring a dramaturgy in which the listener’s emotional horizon is shifted rather than immediately gratified. The technical choices—the careful loop edits, the time-pitch play, the way Charlemagne’s voice is placed inside the drum chemistry—are as much composition as production.

The reception that followed was instructive. The album’s initial life was not a straight line from underground acclaim to pop ubiquity; it built momentum through the scenes that had birthed it, through DJs who treated its movements like secret weapons in their sets. When it checked in at number seven on the British charts, that placement felt less like a commercial coup than a cultural recognition: British popular music was, finally, making room for the sounds that had been doing the most work under disco lights and in basement rentals. The record’s critical afterlife only compounded that effect. Timeless has been archaeologically reappraised, anthologised, and taught as a touchstone in conversations about the history of electronic music.

Part of the record’s resiliency is the way it has been remitted and reimagined. Goldie’s later decision to realise the album working with the Heritage Orchestra to translate jungle’s clipped breaks into string swells and brass dynamics did not feel like a vanity project so much as a logical next step. That orchestral performance, staged at London’s Royal Festival Hall and elsewhere, reframed the album’s architecture in live terms and proved that its emotional framework held in another idiom entirely: a drum & bass record could be scored and conducted without losing the urgency that made it vital to begin with. The orchestral project also functioned as a cultural overture, inviting classical audiences into a conversation with music they might previously have dismissed as purely club-born.

Anniversary editions have kept ‘Timeless’ in the air. A 25th-anniversary remaster arrived with archival material and newly repackaged formats; now, as the record turns thirty, London Records and Goldie’s own channels have rolled out a carefully curated campaign: double-LP formats pressed in white and gold-on-clear, limited cassette editions, and a batch of 500 hand-pressed, hand-stamped records created with The Vinyl Factory—Goldie selecting colourways, Grooverider collaborating at the pressing plant—some proceeds earmarked for War Child. The ecology of these releases is worth noting: they are at once commercial artefacts and ritualised acts of preservation, ensuring that ‘Timeless’ is not only heard anew but also recontextualised in collectible forms that signal its canonical status.

The album’s music and its mythology are inseparable from the people who made it and the losses it memorialises. Diane Charlemagne’s voice, which helped give ‘Inner City Life’ its human core, was mourned when she died in 2015; obituaries in the mainstream press made plain how many paths she had crossed—soul, house, drum & bass—and how central her contributions were to the record’s enduring evocations of grief and grace. The Metalheadz story, too, includes triumph and sorrow: Kemistry’s death in 1999, Goldie’s own public struggles and reconciliations, the hard edges that often accompany lives spent in the music industry. The narrative of ‘Timeless’ is therefore not only technical or aesthetic; it is biographical.

What, then, did ‘Timeless’ do to the shape of electronic music? It widened the permissible vocabulary. Producers who came after borrowed more than drum edits; they borrowed the idea that a club genre could sustain long-form architectures, could borrow from soul and classical tropes without losing its percussive backbone. The record also helped open doors: labels and broadcasters who had once regarded jungle as ephemeral began to take the scene seriously enough to fund and distribute ambitious projects. Its influence is audible in the cinematic tendencies of later drum & bass, in the respectful sampling cultures of modern producers, and in the way emotional cadence began to be a conscious compositional parameter within the genre. Critical lists and retrospective essays continue to place ‘Timeless’ at the top of the conversation, not as nostalgia but as lineage.

For Goldie personally, the consequences of ‘Timeless’ were unpredictable. The album made him a figure capable of crossing into mainstream media: he found acting roles in films such as ‘The World Is Not Enough’ and ‘Snatch’, appeared in television projects, and later turned his own life into two memoirs that traced trauma, reinvention, and the mercurial life of a cultural figure who had refused to be ghettoised. He was awarded an MBE in 2016 for services to music and young people, a bureaucratic recognition that sits uneasily and yet tellingly with his origin story in the margins of British life. The record’s success afforded Goldie cultural capital he used to expand into other domains—visual art, television curation, orchestral projects—and to act as an emissary for the scene he helped steward.

If the album’s thirty-year afterlife teaches one clear lesson, it is this: cultural revolutions are rarely instantaneous; they are sedimentary. ‘Timeless’ arrived out of a subterranean pressure—Blue Note nights, dubplate politics, the invention of studio tricks—and it crystallised into an artefact that altered taste and production in ways both obvious and subtle. It also shows how a record can expand the idea of what success looks like: not simply chart placement, but a reorientation of how a genre thinks about itself and how the wider culture receives that music.

You can pre-order your copy of Goldie’s ‘Timeless (30th Anniversary Limited Edition)’ here.