There is no conventional way to tell the story of Warp Records because Warp has never followed convention. It didn’t start in the usual places—no London lofts or Ibiza terraces. Instead, it materialized in Sheffield, a city wrapped in steel and soot, where underground music was industrial in every sense of the word.

Founded in 1989 by Steve Beckett, Rob Mitchell, and producer Robert Gordon, Warp emerged as something of an accident: an independent label with no fixed genre, no roadmap, and no expectation of longevity. But what it lacked in a clear-cut mission, it compensated for with an uncanny ability to detect the future. That instinct led Warp from the visceral stabs of early bleep techno to the deconstructed electronica that would define its legacy.

Warp’s first proper statement came in the form of LFO’s self-titled single—five and a half minutes of seismic bass, metallic clangs, and otherworldly synths that felt like they had been smuggled in from another dimension. It sold over 130,000 copies, a staggering number for an independent imprint. It also laid the foundation for what would become the label’s sonic philosophy: music that challenged, expanded, and occasionally obliterated the expectations of electronic sound.

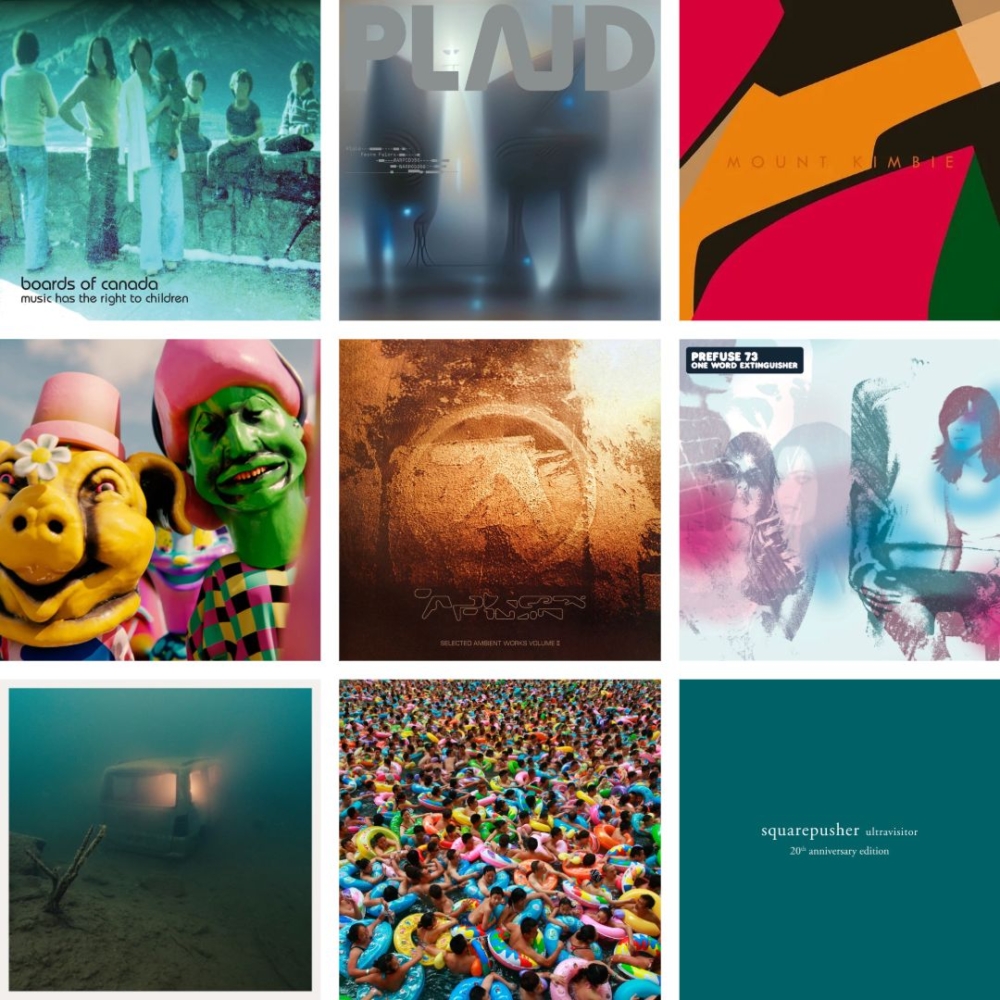

With the ‘Artificial Intelligence’ series in the early ‘90s, Warp effectively rewired the circuitry of electronic music. Aphex Twin, Autechre, The Black Dog—these weren’t producers so much as architects, constructing shifting structures of melody and noise that prioritized texture over accessibility. Suddenly, electronic music wasn’t just for clubs; it was for contemplation, for isolation, for immersion. The term “intelligent dance music” (IDM) was attached, though many of its artists rejected the label. Warp didn’t need categories; it simply existed as an avant-garde current running parallel to the mainstream.

By the late ‘90s and early 2000s, Warp was no longer just a record label; it was a cultural institution. Squarepusher turned bass guitars into alien weaponry. Boards of Canada conjured soundscapes that felt like decayed VHS memories. Broadcast dismantled the past and reconstructed it through ghostly, retro-futuristic pop.

And then, just when Warp seemed to be settling into its role as electronic music’s high-art provocateur, it shifted again. The label’s embrace of left-field hip-hop, abstract rock, and undefinable hybrids led to signings like Flying Lotus, Oneohtrix Point Never, and Yves Tumor. From the shattered jazz of Jlin to the menacing glitch-pop of Kelela, Warp has continued to move where the ground is least stable.

The brand’s longevity is not a result of adapting to trends but of dissolving them entirely. Its visual identity—shaped by the elusive design house The Designers Republic—has been as iconic as its music, embedding itself into the consciousness of electronic music fans in the same way Factory Records did for post-punk. Even to this day, the label’s approach to curation remains as unpredictable as ever, releasing works that feel like cultural events rather than mere albums.

But perhaps the most striking thing about Warp is that, 35 years in, it still feels unknowable. It still feels like an outsider. Other labels have emulated its aesthetic, its meticulous curation, and its refusal to cater to the expected. But the true essence of Warp? That remains untouchable, existing in the spaces between what electronic music is and what it might become next.

To chart the future of Warp is a futile exercise. The only certainty is that it will continue to be a disruption—one that we will likely only understand in retrospect.

Follow Warp Records: Instagram | Facebook | SoundCloud | Spotify